As bird flu cases explode on American farms, top US health experts are sounding the warning over a possible pandemic. Already affecting almost 1,000 dairy cow farms, the H5N1 virus has caused over 70 human infections—including one verified fatality.

The circumstances in the UK are equally alarming. Seven human cases of H5N1 have thus been recorded since 2021; the most recent illnesses were in January 2022 and January 2023. Further concerns regarding the spread of the virus were raised recently when UK officials found the first instance of avian flu in sheep on a Yorkshire farm.

Global Virus Network (GVN) experts underline the threat the virus poses to the US poultry sector and stress the need for quick action to grasp its spread and stop it from getting to people. Noting, “It sure is getting a lot of opportunities,” virologist Dr. Marc Johnson of the University of Missouri said on Twitter that the virus is aggressively seeking to be a pandemic threat.

The GVN is pushing public education on bird flu risks, which may mimic normal flu symptoms. Among mild symptoms include coughing, sore throat, runny nose, body aches, headaches, tiredness, and dyspnea. Severe cases can cause major respiratory problems, including pneumonia, which calls for hospitalization and causes high fevers above 37.7ºC (100ºF).

Human diagnosis of avian flu calls for laboratory tests since symptoms alone are insufficient. For accurate findings, health professionals advise swabs from afflicted persons’ throats, noses, or eyes. Samples taken within the first several days of an illness are the most effective for testing. Lower respiratory tract specimens could also be required to diagnose very sick patients correctly.

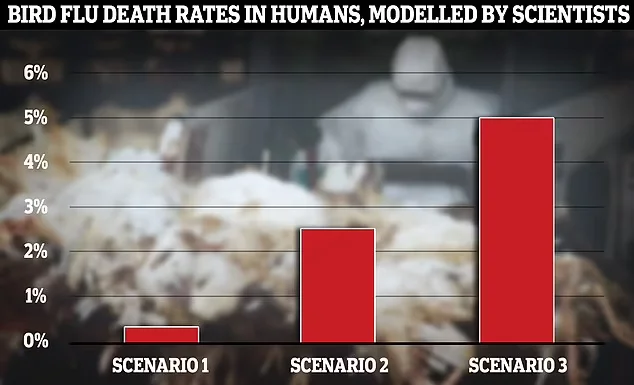

In another scenario, 1% of those infected would be hospitalized and 0.25 % would die, similar to Covid in autumn 2021 (scenario one). The other saw a death rate of 2.5 per cent (scenario two)

Experts keep a tight eye on the potential of avian flu as it looms, stressing the significance of early actions to safeguard public health.

Health officials said it can be difficult to identify the bird flu virus in recovered or less severely sick people. The first known human death from bird flu in the United States occurred in January to a Louisiana resident over 65 years old. The patient had past medical problems and had seen dead and ill birds in a backyard flock. According to genetic tests, the virus might have changed inside the patient, maybe causing more severe symptoms.

This event coincided with California’s declaration of an emergency in response to a bird flu epidemic compromising its dairy cattle. H5N1 has been verified on 645 dairy farms in the state since late August; over half of those cases were reported within a month, therefore highlighting the quick spread of the virus.

Another troubling instance involving an adolescent hospitalization on November 8 following an illness six days earlier surfaced in Canada. Late November saw the teen still in a critical state, needing help to breathe but stable. Research on the origin of the infection showed that the virus did not respond well when one came into touch with reptiles and dogs.

Professionals have voiced worries about the possible epidemic threat H5N1 presents. “If the virus evolves to spread more effectively among humans, we could face another pandemic,” infectious diseases specialist Professor Paul Hunter of the University of East Anglia said. He stressed, though, that there isn’t any data indicating such a change is likely to occur.

Health authorities warn that since the virus cannot survive high temperatures, people are unlikely to get bird flu from well-cooked chicken. Most human illnesses start with direct interaction with contaminated droplets getting into the mouth, nose, or eyes.